The First Shakespeare Movie in Context

With random fun facts about Dracula and a poisoned-rat-infested skull

The First Movies

This may sound like something from a steampunk novel, in which technology exists ahead of its time, like the nineteenth-century computers in William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's Difference Engine, but the earliest Shakespeare movie was made in 1899, while Queen Victoria was still on her throne.

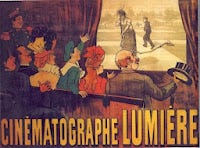

Edison's Kinetoscope had debuted in 1894, and the Lumière brothers had projected a movie on a screen in 1895. The movies made before 1896 were under a minute long and usually recorded ordinary moments like people sneezing, walking in a garden, or leaving a factory. The famous story of the Lumiéres' train movie producing a panic may be apocryphal, but the sheer novelty of moving images was enough to entertain audiences at first.

Even so, the Lumiéres jazzed things up with films that are the ancestors of two popular YouTube genres: a prank (a boy steps on a gardener's hose and then releases it when the poor fellow looks down the nozzle) and a fail (a man tries repeatedly to get on a horse and keeps falling off). Edison's film of Mary, Queen of Scots, getting her head chopped off, with its costumes and special effect, represented greater possibilities, and in 1896 Alice Guy Blaché filmed the first fantasy movie: a woman dressed as a fairy pulling babies out of giant cabbages. The magician George Méliès, who appears as an old man in Martin Scorcese's Hugo, followed with the first horror movie, the three-minute-long Devil's Manor, in which a bat, a devil and his helper, a cauldron, a skeleton, and ghostly women appear and disappear every couple of seconds until the devil is vanquished by a man with a cross.

While Méliès made fantasy spectacles with his Star Film Company, on the other side of the Atlantic the Scotsman William Kennedy Dickson, who had helped develop Edison's Kinetoscope (indeed, he may have done most of the work), made documentaries and fiction films for his American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. After filming Niagara Falls, the world-famous Chinese politician Li Hongzhang, President McKinley, and Rip Van Winkle, among other subjects, Dickson went to Europe in 1897 to run Mutoscope's British branch. In 1898 he filmed Pope Leo XIII and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and the following year directed the first Shakespeare movie: four scenes from King John starring Herbert Beerbohm Tree.

Celebrity

Dickson's King John resembles his movies of a president, pope, and queen in that Tree was a celebrity. The man, rather than his performance of King John, probably drew most of the audience. In the United States, the movie was called Beerbohm Tree: The Great English Actor, which shows that American audiences probably saw it simply to watch a famous actor acting.

King John may seem an obscure choice for Tree's performance. There's no record of it being staged before the eighteenth century, and it's rarely been performed in the twentieth and twenty-first. But according to Jeffrey Richards (119), it was a staple of the Victorian Shakespeare repertoire. Its combination of parading royal retinues, battles, and a histrionic death scene would have been like honey-stalks to sheep for Tree, the last of the great Victorian actor-managers, the heir to Henry Irving (random fun fact—Irving's secretary Bram Stoker used the actor's charismatic personality as a model for Dracula's).

Tree had been performing King John in Her Majesty's Theatre, which was built for him two years earlier. The British Film Institute suggests that Tree made the film to advertise his stage performance, but presumably he was also happy to join the growing list of international celebrities that Dickson had filmed.

That list included the most famous American comic actor performing his most famous role: Joseph Jefferson as Rip Van Winkle. Jefferson had played Rip in the United States and Australia before Dion Boucicault wrote a version for him in 1865 that created a sensation in London. For the rest of his life, Jefferson performed the play to packed audiences. In 1896, when Dickson filmed him pantomiming eight episodes, the actor was still famous throughout the English-speaking world.

King John

Dickson's King John resembles his Rip Van Winkle in that both have celebrated actors performing versions of national literary classics. But while many people today have read Washington Irving's short story—or at least know its basic outline—few have read Shakespeare's King John. Its story is unfamiliar. People encountering Dickson's Rip Van Winkle can usually follow it without titles but would be baffled by his King John, even if all four scenes had survived.

As it is, only a fragment of the death scene remains, and many viewers will see it as simply an actor hamming it up as a dying king in a play they've never heard of. The name "King John" conjures up the villain of the Robin Hood stories (cue up Steely Dan's ironic "Kings") or the autocrat forced to sign the Magna Carta, neither of which resembles Shakespeare's character, who initially demonstrates fortitude—as well as the patriotism and anti-Catholicism much admired by Victorian English audiences—before becoming a vacillating weakling.

In the final act, John is poisoned by the monk who was also his food taster. As a result of this suicide-poisoning, the monk's "bowels suddenly burst out," so we anticipate a similarly gruesome end for the king. When we hear that the poison has driven him insane—as his son Prince Henry describes it, Death's "siege is now / Against the mind; the which he pricks and wounds / With many legions of strange fantasies"—we anticipate Lear-like ravings for John's final scene.

Yet he speaks eloquently at first, recovering some of the dignity he's lost throughout the play, a pattern reminiscent of Othello. In his second speech, the madness takes hold as he begs wildly for someone to relieve his fever by commanding winter to "thrust his icy fingers in my maw," rivers to "take their course / Through my burned bosom," and the north winds to "kiss my parchèd lips." Prince Henry says that he wishes his tears could relieve his father's agony, but John rejects this, saying that the salt in those tears is hot. There's a hell inside him, and the poison is a fiend tyrannizing over his blood.

At this point, John's nephew, the Bastard, arrives, and the king recovers his wits, clinging to life to hear the Bastard's news. The Bastard reports that their enemy, a French prince, approaches but that they can't defend themselves because the English forces have been destroyed by a flood. Hearing this, the king dies. We soon learn that the news is out of date—the French prince has agreed to a peace. King John has died suffering needless despair.

The Fragment

This twist is missing from the surviving fragment of Dickson's film, which opens with John's first speech and ends before the Bastard's entrance. The set, which was in Dickson's studio rather than Tree's theater, consists of a bushy tree and a backdrop painted with Romanesque arches, indicating that we are in an abbey garden.

On John's left and right stand two minor characters: Lord Bigot (seriously, that's his name) and Pembroke—we have no way of knowing which is which. Either could as easily have been another minor character, Salisbury (William Longespée), but the British Film Institute's cast list indicates that Salisbury isn't in the fragment, which makes my second random fun fact even more random: when the historical Salisbury's tomb was opened in the eighteenth century, a dead rat full of arsenic was found in his skull. Presumably, Salisbury was poisoned with arsenic, and the rat crawled in to feast on his brains. This weird fact supplied the children’s book author Cornelia Funke with inspiration for Ghost Knight.

.According to a scholar cited in a yellowing 1919 Variorum Shakespeare in the Chico State library (I cut the pages in 2014, so I was the first to read this copy in over a century), arsenic is also the poison that kills Shakespeare's King John: "The extreme debility, the thirst, the burning of the mouth and throat symptomatic of arsenical poisoning find their adequate expression" in John's ravings (416). Arsenic and its effects were well known in the sixteenth century, but Shakespeare never mentions it specifically, nor do his sources. The Second Series Arden edition lists these as John Foxe's Actes and Monuments (aka The Book of Martyrs, which provided anti-Catholic material), an anonymous play, and three chronicles, including Shakespeare's favorite for his histories—Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Holinshed proposes a possibility besides poison for the cause of John's death. The "grief" resulting from the loss of English forces brought on a fever that combined with "immoderate feeding on raw peaches, and drinking of new cider" to weaken his body. In the end, it was "through anguish of mind, rather than through force of sickness [that] he departed this life." I think Shakespeare combined this suggestion with the poisoning story for his version of the king's demise. While the poison destroys John's body and mind, the Bastard's outdated news becomes the scissors that finally cuts the "one thread, one little hair; / . . . one poor string" (5.7.54-55) by which the king clings to life. Like Lear, John thus dies ultimately because of grief, but while Lear grieves loudly for the loss of his daughter—"Thou'lt come no more, / Never, never, never, never, never!" (5.3.306-307)— John grieves silently for the loss of English forces and the impending loss of his kingdom.

Unless a director wants to leave this moment ambiguous, it calls for great acting. The Bastard should show an understanding of the pain he's causing a dying man, and, without speaking, the king should show that the news kills him. At the least, he should show that he hears what the Bastard says. Otherwise, we lose the powerful situational irony of him dying as he hears false bad news.

This effect is more easily accomplished on screen than on stage. In the 1984 BBC production, director David Giles holds a close-up of John's face so that we see he hears the news that the Bastard delivers in a hushed, slightly quavering voice. Quiet voices and close-ups aren't possible in a theater, where actors need to speak and use body language that will be understood in the back rows. Her Majesty's Theatre held at least 1700 people, so voices needed to be loud and gestures exaggerated, which is why we can't be sure that the melodramatic acting style we see in Dickson's film differed greatly from what happened in Tree's theatre.

Nevertheless, Tree and his fellow actors knew that their body language would need to convey everything in the film. They were deprived of more subtle effects since Dickson didn't use close-ups. (His contemporary, the showman and spiritualist G. A. Smith, would begin experimenting with these the following year in films like "Grandma's Reading Glass.")

1899 Best Actress Nominee

It would have been interesting to see how Tree and Lewis Waller, the famous Shakespearean actor who played the Bastard, handled John's final moments, but, though the web is full of commentary saying otherwise, the surviving fragment of Dickson's film ends before John's death. What we have instead are John's first three speeches and Prince Henry's failed attempt at comforting his father.

In Tree's theatrical production and Dickson's film, Henry was played by the twenty-one-year-old Dora Tulloch, who at this point in her career had adopted the stage name Dora Senior. As a child, Tulloch was famous for poetry recitations: The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art described her at twelve as "a very clever child, whose recital of Tennyson's ballad, 'The Revenge,' was so good as to force her to give [Robert Southey's] 'The Well of St. Keyne' by way of encore" (4 June 1892: 657), and the Musical Times predicted that "with further study and perseverance she may attain a high position as an elocutionist and possibly as an actress" (1 March 1892: 167). Her performances as Prince Henry were the apex of her career since she quit acting professionally shortly afterward.

Many people know that boys played women in Shakespeare's day but are surprised to learn that women regularly played boys and men in nineteenth-century Shakespeare productions. The most famous American actress of the first half of the century, Charlotte Cushman, was celebrated for her Romeo (see Lisa Merrill's When Romeo Was a Woman), and the most famous actress of the second half, Sarah Bernhardt, created a sensation with her Hamlet. A year after Tree and Tulloch performed in King John, Bernhardt would become the first actor to play Hamlet on film, in a one-and-a-half minute version of the duel with Laertes, which curiously ends with Hamlet dying and being carried off the stage—Claudius, Gertrude, and Fortinbras never appear.

In general, Victorian women played boys or very young men, as Tulloch does in Dickson's film. We see her standing to Tree's left, holding her necklace as Tree delivers John's first speech. As he speaks of the hot summer inside him, he pulls open the neck of his gown, then reaches toward Tulloch, who takes his hand as she asks, "How fares your majesty?" Tree writhes away, flailing as he madly begs someone to command the elements to relieve his fever. After Tulloch kneels beside him—"O, that there were some virtue in my tears / That might relieve you!"—Tree touches her face with the side of his hand. He jerks his hand away and wipes it, saying of the tears, "The salt in them is hot" (45), then grabs his breast as he speaks of the fiend tyrannizing over his blood . . .

And there the fragment ends.

Now let’s watch it

I suggest turning the sound off. This is usually advisable when watching silent films since the soundtracks rarely fit and are often distracting.