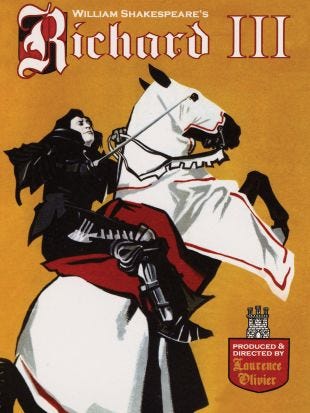

Laurence Olivier's Richard III: Titles and Opening Scenes

David Garrick's Heir

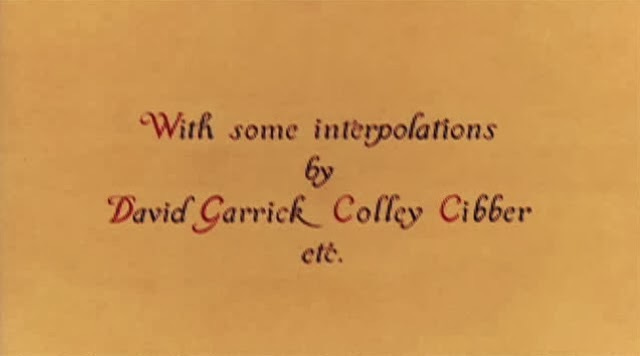

Laurence Olivier opens his 1955 Richard III with stirring tympani and trumpets and titles reading "Laurence Olivier Presents Richard III by William Shakespeare With some interpolations by David Garrick Colley Cibber etc." Viewers unfamiliar with English theater history might suppose that Garrick and Cibber were screenwriters and that the title resembles the one that supposedly opened the 1929 Taming of the Shrew with Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., and Mary Pickford: "Written by William Shakespeare with additional dialogue by Sam Taylor." (Erskine 341). In fact, Garrick was an eighteenth-century actor and Cibber an eighteenth-century playwright, and Olivier's reference to them gives us our first hint about the relationship between his movie and Shakespeare's play.

For almost two centuries, from the beginning of the eighteenth to the late nineteenth, the most familiar version of Richard III was by Colley Cibber, a theater manager, actor, and playwright best remembered as the Dunce in Alexander Pope's mock epic.

Cibber made two large structural changes to Shakespeare's play. First, he began with Richard murdering the Lancastrian king Henry VI, the penultimate scene in The Third Part of Henry VI, the play that precedes Richard III in Shakespeare's first tetralogy of history plays. Second, Cibber eliminated one of Shakespeare's greatest characters, Margaret of Anjou, who appears in all four plays, beginning (in The First Part of Henry VI) as a young bride and ending (in Richard III) as a kind of living ghost, haunting and cursing the Yorks.

Like Cibber's Richard III, Olivier's starts with a scene from The Third Part of Henry VI—the last rather than the second-to-last—and eliminates Margaret. Olivier also includes Cibber's lines, "Off with his head. So much for Buckingham" and "Richard's himself again," lines made famous by the actor-manager who succeeded Cibber at the Drury Lane theater: David Garrick, the most celebrated English actor of the eighteenth century.

As the best-known English actor of the twentieth century, Olivier probably considered himself to be Garrick's heir, especially when performing Garrick's most famous role. The connection may have been in film director Alexander Korda's mind when he commissioned Salvador Dalí to paint Olivier in costume as Richard.

Just as William Hogarth's painting of David Garrick as Richard is the most familiar portrayal of that actor, so Dalí's is now the most famous of Olivier. Those who've seen Olivier's film will recognize his hat and the hand with two missing fingers. The ring on his pinky may allude to the ring Richard gives Tyrell when commissioning the little princes' murder. His double face represents both Richard's double nature and the actor behind the role. In the background is one of Dalí's Spanish-looking landscapes, now standing for Bosworth Field, which Olivier recreated outside Madrid.

Edward's Coronation

As the film's title sequence indicates, in recreating this story, Olivier drew not just on Shakespeare's play but on the theatrical tradition surrounding that play. He also drew on Richard's legend. The final titles tell us: "Here now begins one of the most famous and at the same time the most infamous of the legends that are attached to The Crown of England."

Olivier may have stressed the legendary aspect of the story in part as a response to defenses of the historical Richard. Such defenses must have existed when the Tudor legend of Richard's deformity and wickedness first took shape. They began in earnest with Horace Walpole's Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third in the eighteenth century and saw a resurgence after the publication of Josephine Tey's mystery novel The Daughter of Time in 1951. In 1954, the actor Richard Clarke formed the Friends of Richard to defend the last Yorkist king. The following year, after the release of Olivier's film, Clarke claimed Olivier told him he included the shot of the inscription on Richard's garter—"honi soit qui mal y pense," "shame on those who think of ill of it"—near the end of the film "especially for you people."

Appeasing Ricardians no doubt mattered less to Olivier than drawing the audience into the film's atmosphere. The title sequence does this with medieval-looking calligraphy, border decorations, and illustrations that give us the sense that what follows is a filmed version of a tale from a medieval manuscript. Olivier's strategy here resembles what he does in his Henry V (1944), where he begins with a playbill for the original Globe performance, moves to a shot over a model of London, then to the Globe itself (Tom Stoppard and Marc Norman may be imitating this opening in Shakespeare in Love). When the performance in the Globe moves to a more realistic setting, we get the sense that what we are watching resembles what would be happening in the original audience's imagination. Olivier reinforces that sense at the end of the film when he returns to the Globe performance.

Olivier similarly bookends his Richard III by beginning and ending with the legendary crown. In the opening titles, a drawn crown dissolves into a filmed one (a trick Olivier reverses at the film's end). The camera pans down to show us that this crown is actually an enormous sculpture suspended over the real crown, which is being lowered onto the "son of York" who is about to become Edward IV. A different angle shows us the other Yorks and their followers, lowering still more crowns, "victorious wreaths," onto their own heads. (There are far too many crowns here.) We see Richard from behind, his crown in front of the royal one. The framing hints at his ambition, at which crown he wishes were settling on his head. Later Olivier as Richard will reinforce this impression by carelessly handing his crown to a servant, who drops it; Olivier will register annoyance so mild that we will know how little he values his inferior crown, the sign of his present, lower position in the Yorkist hierarchy.

Olivier introduces the hierarchy's factions after the crowd chants "God save King Edward the Fourth! Long live King Edward the Fourth! May the king live forever!" Richard looks over his shoulder, giving us our first sight of his huge triangular nose. Another shot reveals that he's not looking at us but at his ally Buckingham (Ralph Richardson), who in turn looks at Richard's first victim: Clarence (John Gielgud), who stands with piously folded hands, blinking, his insipid expression contrasting with Richard's and Buckingham's knowing ones. Clarence turns and looks at his mother the Duchess of York, at the little princes, and at Queen Elizabeth and her brother and sons by her first marriage. In a few quick shots, we have been introduced to every character that stands between Richard and the throne.

As these characters leave the coronation chamber, we're introduced to a character who doesn't appear in Shakespeare's play: Edward's mistress Jane Shore. She moves her hand toward the king, who almost touches her cheek with his scepter. Jane's eyes gleam, and Queen Elizabeth's face freezes as she moves with her husband into the next room, where Olivier gives us the last scene of The Third Part of Henry VI. Before Edward speaks of his son inheriting the crown, Jane slips behind the throne. When he announces celebrations that suit the "pleasure of the court," we see her in the right foreground. As the celebrations begin with a procession through the streets, we see her following in a litter.

Her character highlights Edward's loose morals, which Richard will use to delegitimize his son's succession. In later scenes, she underscores the weakness that allows Richard to manipulate his brother. For example, after Richard gets Edward to sign Clarence's execution order, we see Jane hand the king a goblet of wine: we understand that, distracted by his pleasures, Edward isn't paying adequate attention to serious matters. We see this again when he tries to make peace among the Yorks: as his wife addresses them with her back to her husband, Edward takes the opportunity to kiss Jane's hand. After his death, Jane plays a similar role in Hastings's downfall, distracting him from warnings that might save him from destruction.